Considering the Show “Catch a Contractor”

Architecture and television isn’t anything new. Between HGTV broadcasting a smorgasbord of realty TV shows 24 hours a day (Love it Or List It, Flip This House, The Property Brothers) along with the manipulatively tear-jerking Extreme Makeover: Home Edition, Americans really love watching remodels. At least, when they’re only 21 minutes long.

There are countless articles (link, link) out there about the unrealistic scenarios these shows project. Often times, labor is excluded from the price listed for renovations and don’t get me started on the timelines. Most of these homes are preassembled. Paint takes time to dry, so does sheet rock mud and concrete isn’t completely set until 30 days after being poured so it can be fully loaded until then. Really–how you finish a house in less than 30 days?

I’m looking at you, Ty Pennington.

But Adam Carolla’s To Catch a Contractor appealed to me. It’s a different approach—showing the dark side of failed renovations—but with the same reality TV happy-ending pay off. Carolla finds homes in the middle of renovation that were abandoned by contractors.

The only experience I had with Adam Carolla before watching Catch a Contractor was with his radio station, Love Line, which my daughter used to listen to. I am, admittedly, not the biggest fan of his and his pop-culture steeped humor or his misogynistic tendencies. But I am interested in the smarter side of television and architecture.

In his show, Carolla goes through the home with the family and comments on the damage. And I must admit, Adam Carolla really knows his stuff—his commentary on masonry, pressure-treated lumber, electrical outfitting and the use of proper materials impressed me. He also offers sage (albeit cookie-cutter) wisdom, like “never give the contractor more than 50% of the money” and “always ask for accounting.”

There are two scenarios Carolla offers the family. Either they will attempt to find the contractor and make him do the work and do it right. OR if they can’t find him, Carolla’s team will take over renovations and help the family in question take legal action.

In true reality television indulgence, once the contractor is found (and he always is), he is publicly humiliated in a confrontation. Present are the clients, Carolla and his personal contractor (who resembles someone that might crush plaster into dust with his bare hands).

The contractor is then brought through his abomination of a project. Under the watchful and critical eye of Carolla and his contractor, the original contractor must fix his mess. About three television minutes later, we cut to the happy family seeing the finished renovation.

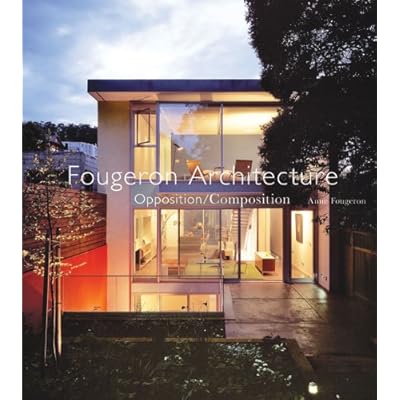

As an architect, I maintain a precarious relationship with contractors. You find a lot of bad ones—overpriced, always behind schedule; they skimp on materials or fine details (I cannot count the amount of misaligned windows I have caught) and some even abandon the job half finished… But, when I find a good one, I hang on tightly as I can (like Thomas George Construction, who worked with me on The Fall House). Their watchful eye, skills and knowledge are intrinsic to my project getting done. I can’t be present at a site 10 hours a day and I must fully trust the person I am handing the design and money too.

Plus, a little public shaming to those who give contractors a bad name can’t hurt, right? And it is really good after a frustrating days dealing with a not so good contractor, beer in hand.